for La Lettura - Corriere della Sera

Visual

Linguistics

2020 - Present

MAPPING SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTS OF LINGUISTICS FOR THE LARGER AUDIENCE

Within the Sunday cultural insert of Corriere della Sera newspaper, Visual Data column has been for more than a decade an important reference for information design, promoting an experimental approach to visual rendering of data.

This section showcases a growing collection of my data visualization around the basic concepts of linguistics. Many of these works are based on qualitative datasets, in order to illustrate the fundamentals of linguistics which by their nature cannot be displayed as metrics.

I am the sole author of the original idea, the researcher and editor of the dataset, and the designer

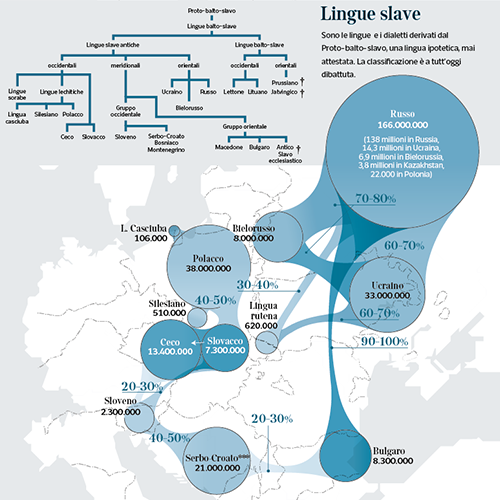

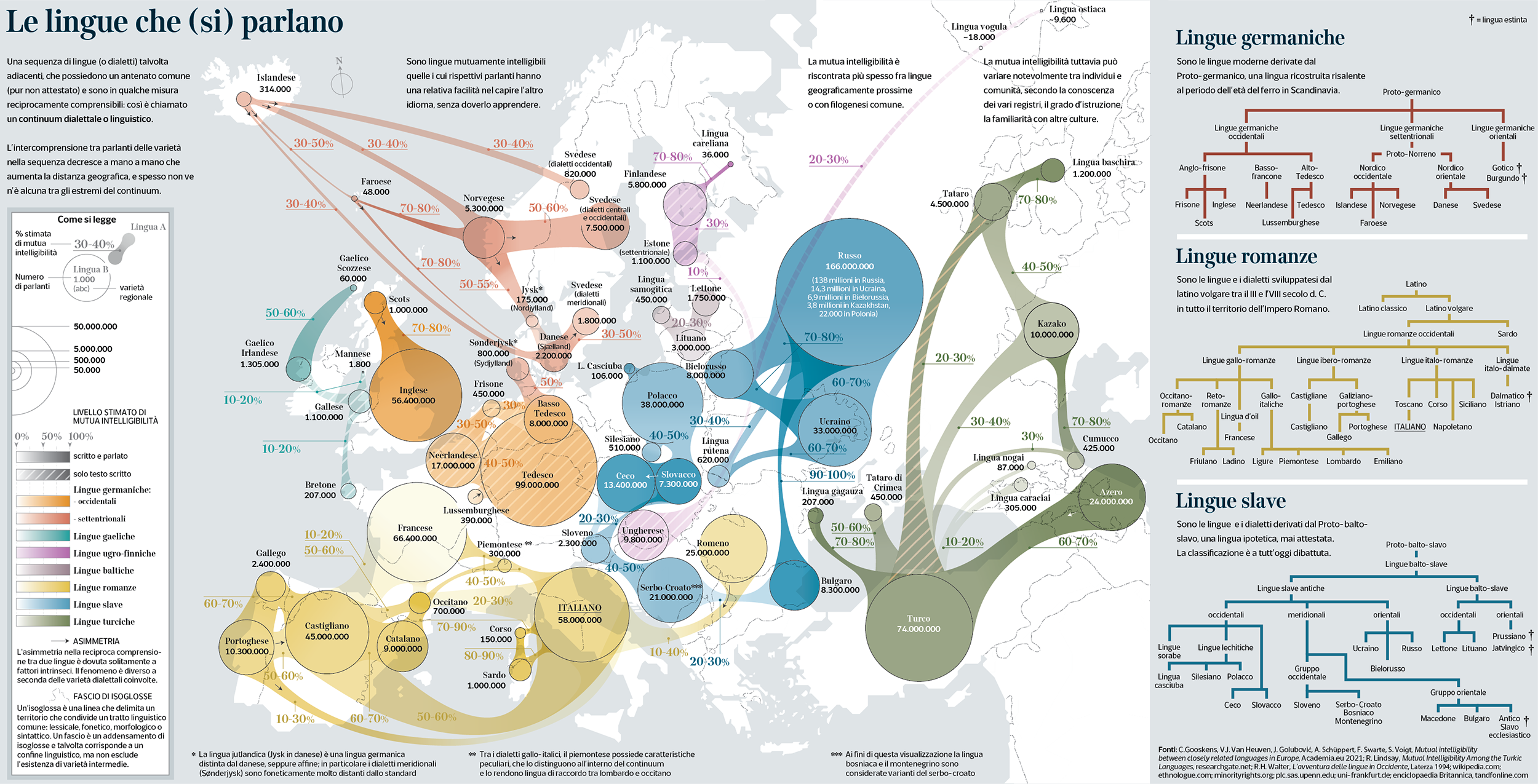

Reciprocal Intelligibility Among European Languages

A topic relatively poorly addressed by synchronic Linguistics is that of intelligibility between different languages, or between dialects and languages.

In reality, both languages and dialects (with all the contentions that this initial distinction entails) have been no longer considered by the scientific community as unitary and immutable entities, for at least 150 years. And this has led in turn to a general reconsideration of the subject matter.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, thanks to the studies of Meillet, Gilliéron, and Weinreich, many surveys were collected all over Europe and subsequently organized in the form of linguistic maps to outline the topographical distribution of phonetic variations and the overlapping of lexical elements. Dialectology was established as a study of linguistic phenomena common to the varieties of a dialect or to the various dialects of a linguistic group. And shortly thereafter, even the ‘national’ languages were reconsidered in a new light, in all their complexity.

Many years later, the variability of linguistic phenomena is now at the center of countless studies, much more than unity, analyzed in time, space, and social stratification, in the range of stylistic and functional contexts. In this respect, the distinction between dialects and languages is also questioned by many scholars.

The synchronic investigation made it possible to formulate some revolutionary linguistic principles for the time:

- there are no precise boundaries between one variety and another, but only areas of diffusion of specific phenomena;

- the innovations are punctual, they arise through the work of individuals, and they do not spread uniformly but, if anything, they radiate along the communication routes, from center to center and only secondarily in rural areas. They suffer from natural barriers, social differences, and political and religious boundaries.

The possibility of inter-comprehension between different languages and dialects is something that every speaker who moves on the edge of a compact linguistic area, or who for some reason comes into contact with other related languages or dialects, experiences and appreciates. Commonly widespread in the population, and felt by the most curious and interested individuals, it is a phenomenon typically noted where the languages used have been implanted for a long time: in addition to the examples provided by this visualization, cases of Indo-Aryan languages are known in large areas of India, the varieties of Arabic in North Africa and Southwest Asia, the many varieties of Chinese. Linguist L. Bloomfield called these dialect areas, and F. Hockett called them L-complexes.

Studied from the diachronic point of view, a dialect continuum corresponds to the (now stratified) effects of a series of linguistic innovations branched out in the form of waves. It happens that a variety within a continuum asserts itself as a standard language, and influences in the form of a roof language as a reference for the other varieties present in the area, attracting some phonetic, morphological, or lexical outcomes.

The degree of inter-comprehension between different languages and dialects is therefore an individual phenomenon, which occurs at the level of the single speaker, and as such difficult to frame for Linguistics. Therefore any computation of mutual intelligibility is indicative because it shows only illustratively how accurately the populations speaking different languages or dialects can understand each other’s speech (or in some cases only the written language), without the contribution of a previous study.

This visualization aims at render the average range of mutual understanding, on a very broad and approximate scale. The circle size represents the amount of speakers per each language, and colors represent the language families assessed by the study. On the right side, the family trees account for the phylogenetic relationships between languages pertaining to the Germanic, Romance, and Slavish branches.

This visualization has been showcased in 2023 Information is Beautiful Awards’ shortlist.

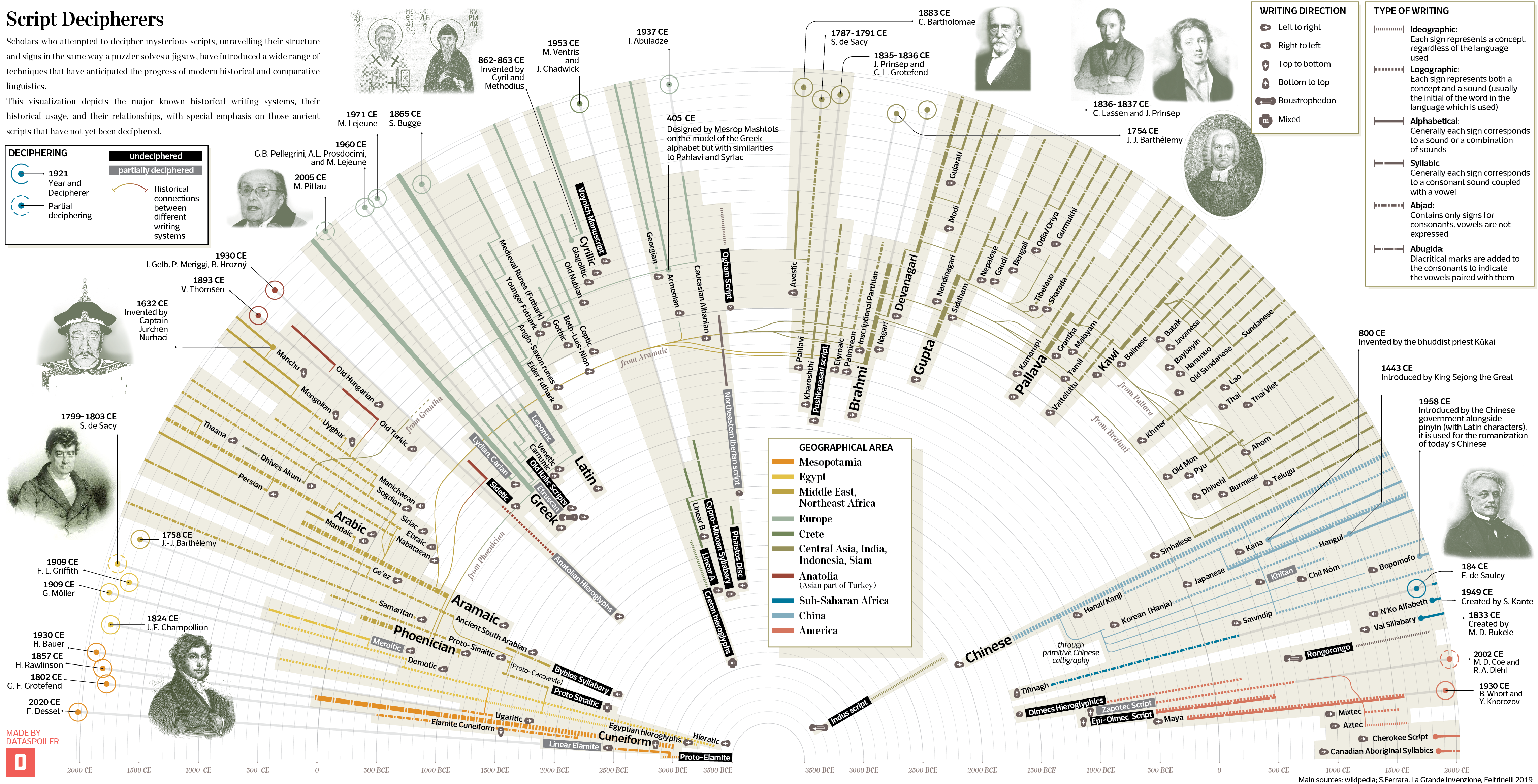

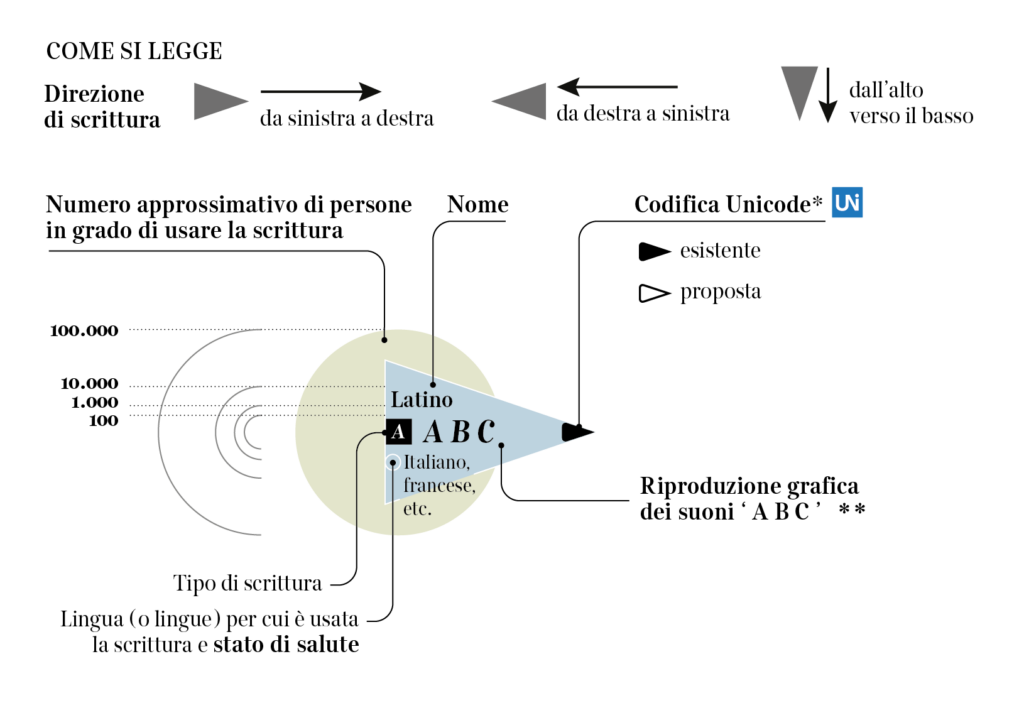

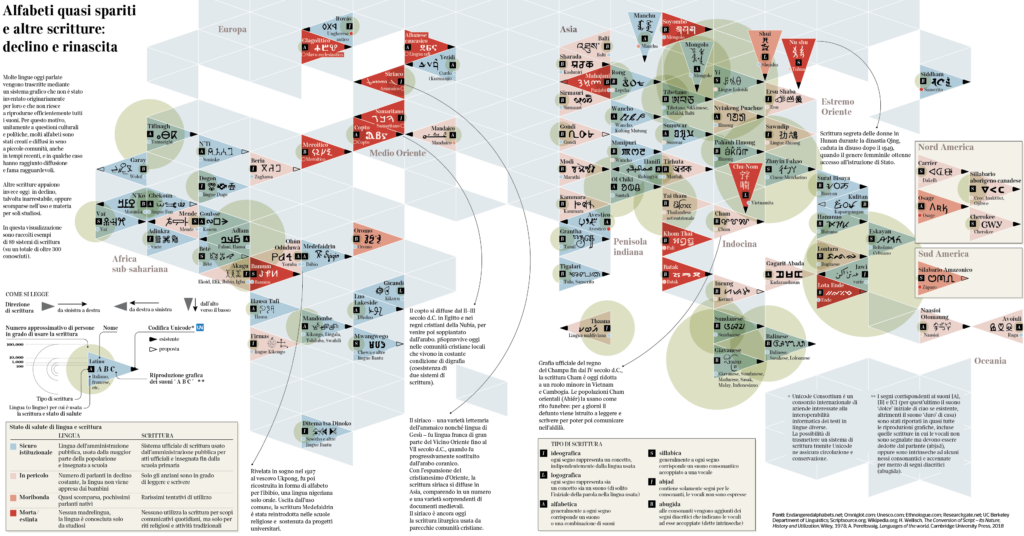

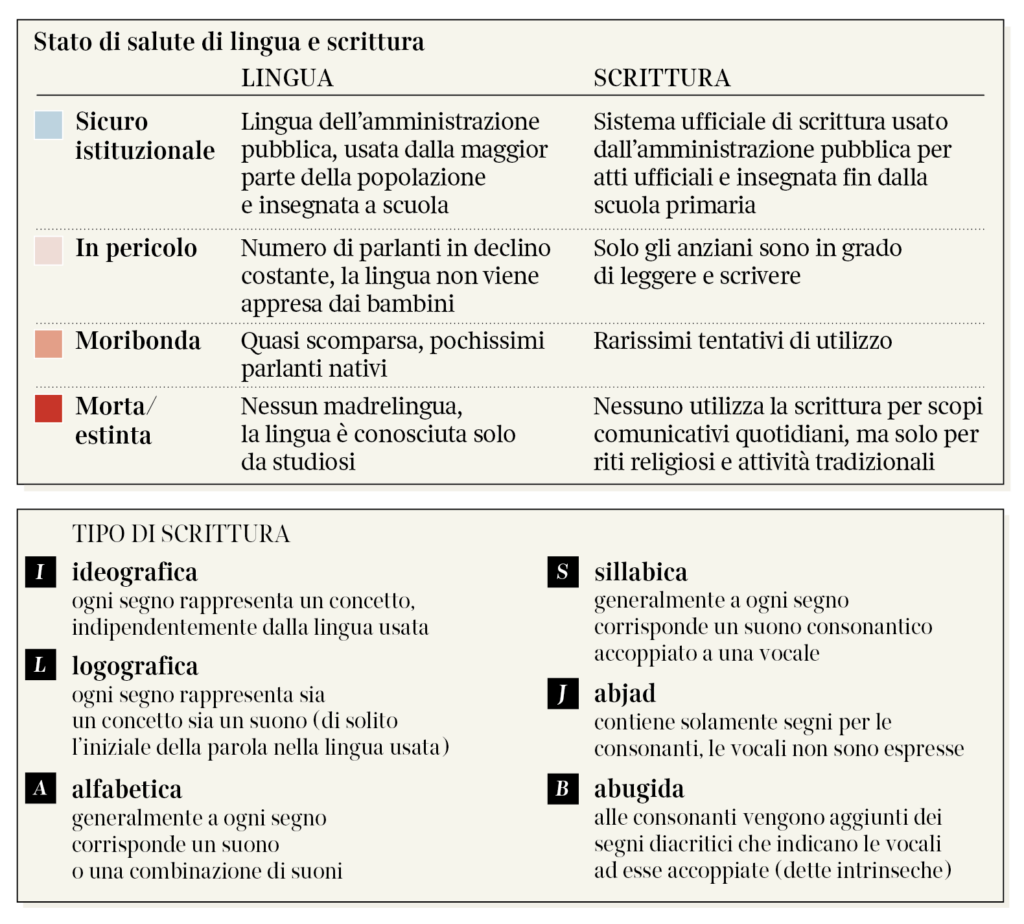

Endangered alphabets: decline and rebirth

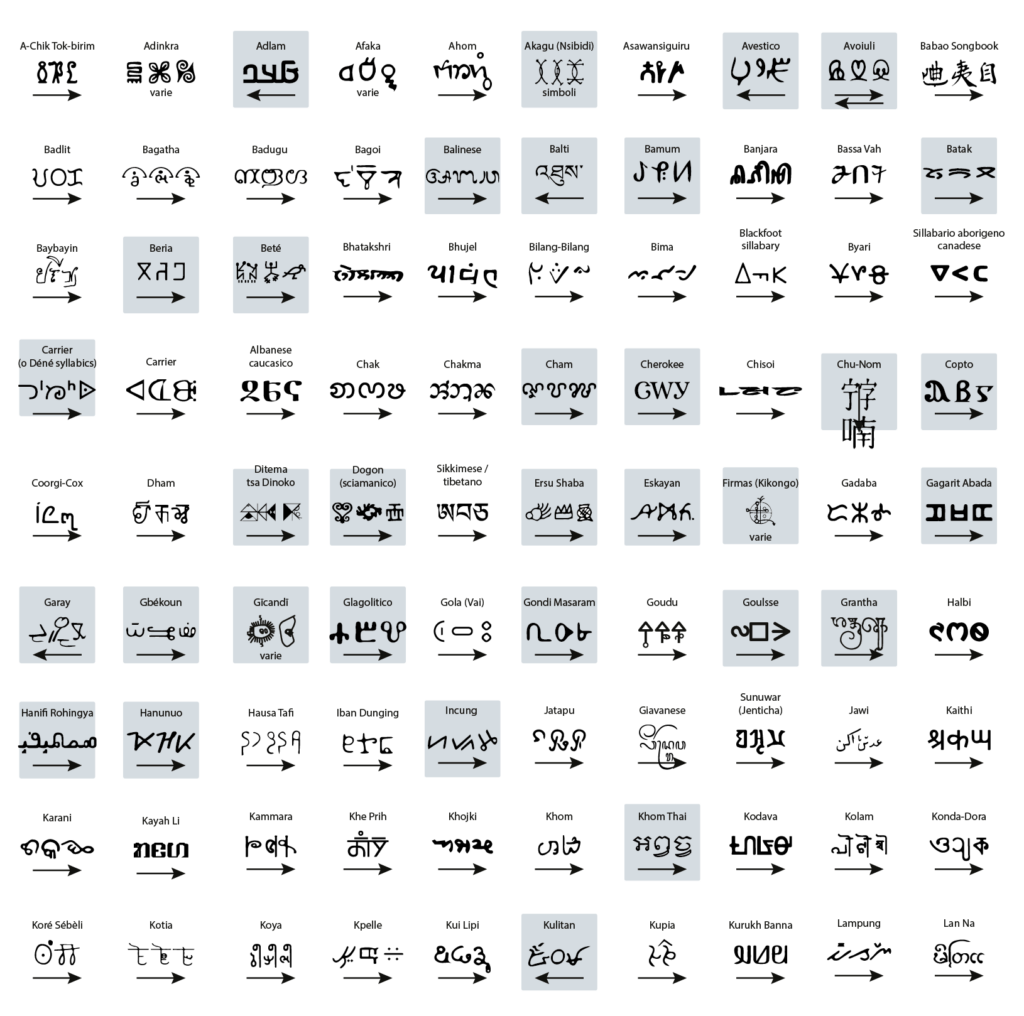

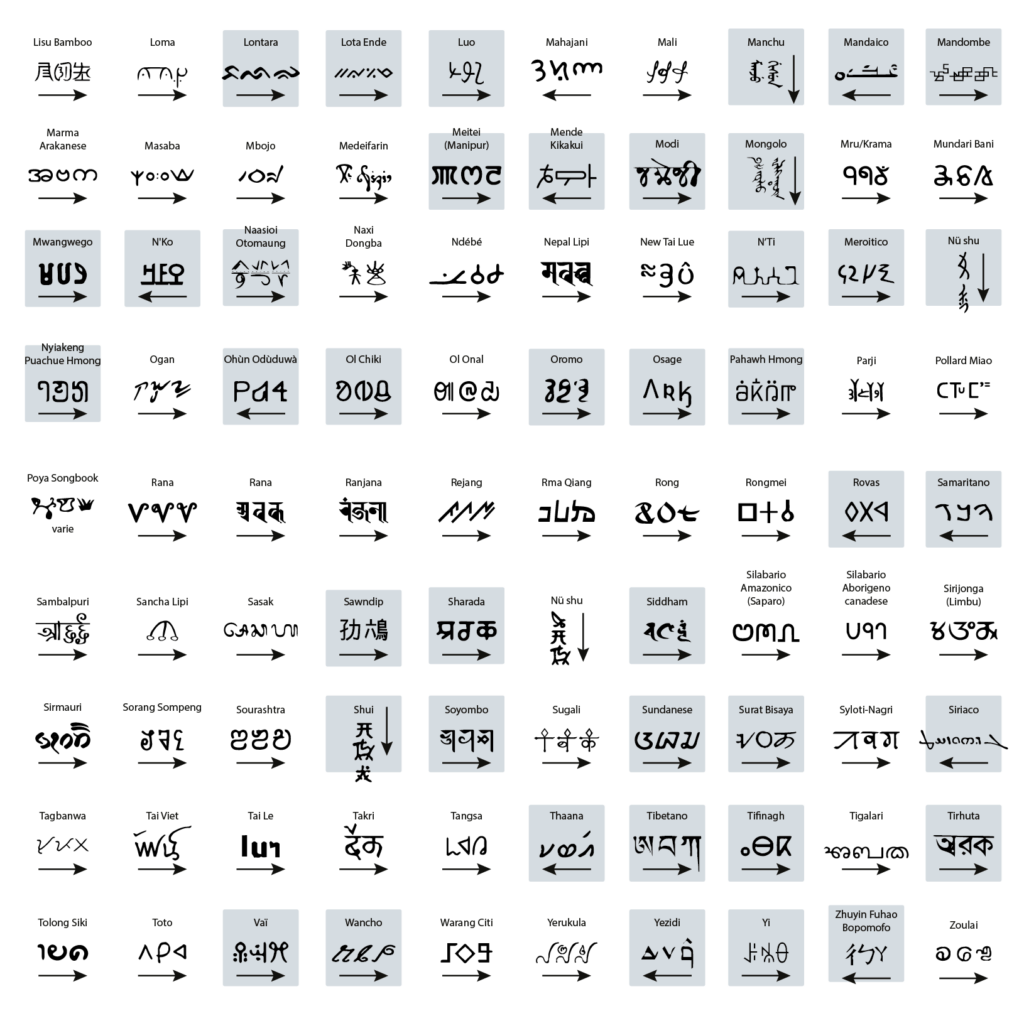

Through the ages, many writing systems have been adopted around the world, and many have gone deeply endangered, fading away from use and recognition even by their very speakers. Especially in the last 5 decades. This visualization aims at showing the main features of a few of them, around 90 out of 200 currently classified as endangered, moribund, or definitely extinct.

No spoken language is inherently entangled to any specific writing system (nor is to a script, which may be seen as a collection of characters used for writing a specific language thanks to some adaption), and many languages have multiple scripts, including Punjabi, Serbo-Croatian, and Japanese, as examples. Also, outside the Americas and Europe, most people know and use more than one script, sometimes three or four, without necessarily speaking more than one language.

Writing systems can be classified according to their structure (like in this visualization), or according to their sociolinguistic function, that varies from orthography, to

Based on these definitions, it can be arguably inferred that a script can be borrowed fully or partially to write a language for which it had not been originally invented or developed. Indeed, most languages are written in a script that had not been primarily invented for them but is only known to and accepted by its users. Throughout human history, many writing systems have been, by and large, used, borrowed, even imposed, and eventually abandoned. Many of these survive in the form of historical tradition, recovered through philological studies or enclosed within restricted communities. Many are in real danger, crushed by the use of more widespread alphabets (above all the Latin alphabet)

Sloppiness, declining self-respect, or desertion of a writing system are some of the most disturbing examples of cultural loss, but they are not the only reasons why scripts are dropped out of use. Endangered, moribund, or even perished alphabets are often the echoes of lost nations, cultural oppression over loose and isolated people, and people no longer in communication. Fragmentation is the dry rot of an alphabet — the loss of control, the loss of a critical mass.

On the other hand, several groups across the world, bonded by cultural interests, have invested time and resources in reenacting ancient scripts that fit well with the language they speak, or in inventing new writing systems for the sake of reconnecting sparse people and affirming their relations.

I checked the state of health of almost 200 writing systems that in most cases are not officially used by public institutions, are not taught in schools or if they are taught, they are mostly in the form of a historical repêchage, whose cultural trace is getting lost and which tends to remain only as an ethnic mark.

However, they are not all sad stories: some of these writing systems such as Chak in Myanmar are recovering thanks to the work of scholars, translators, and teachers. The last word about their legacy still has to be written.

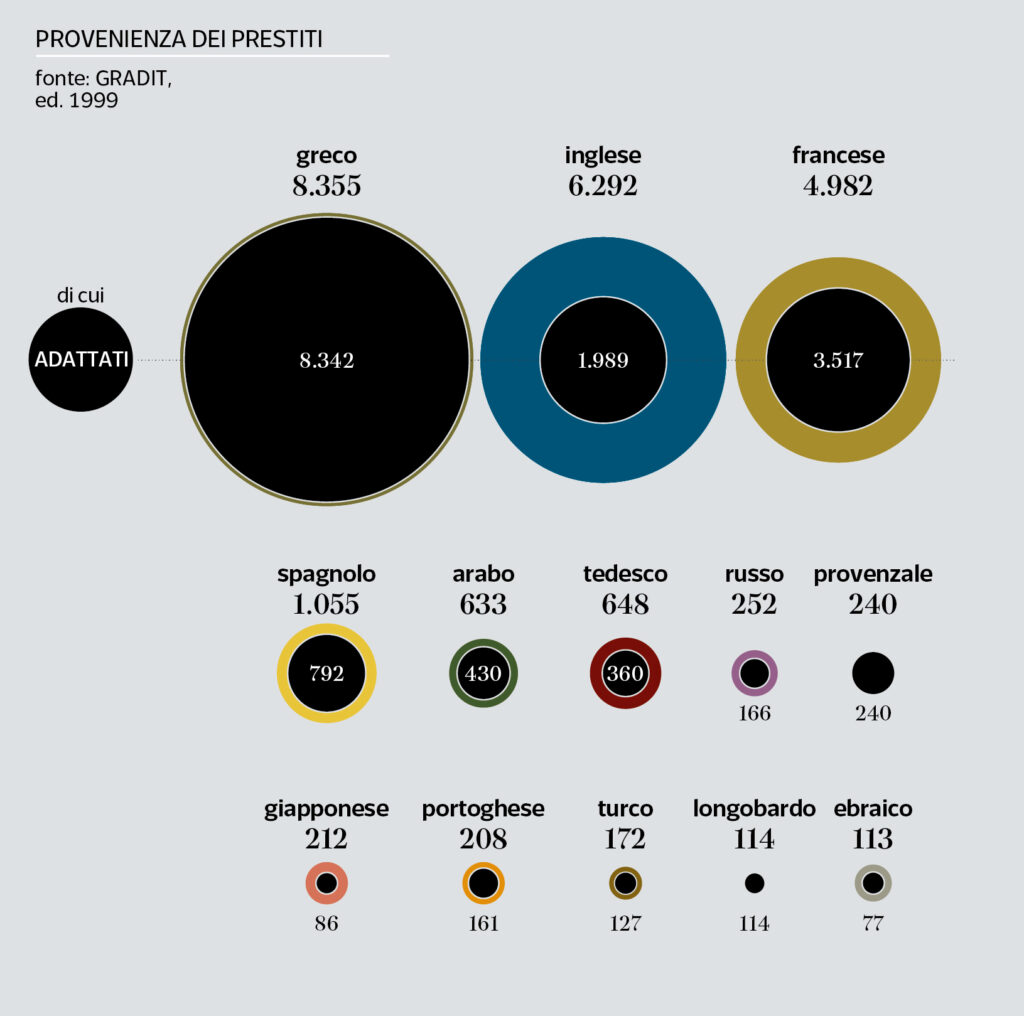

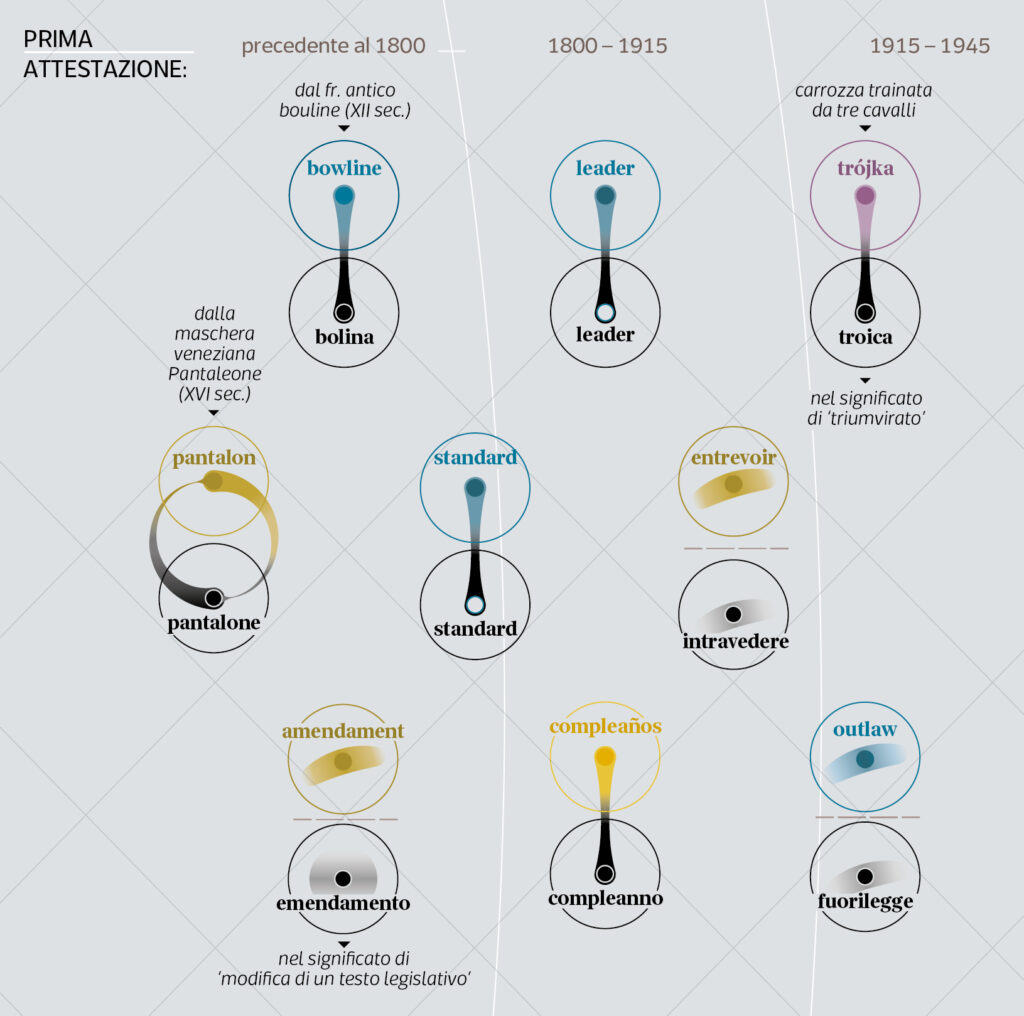

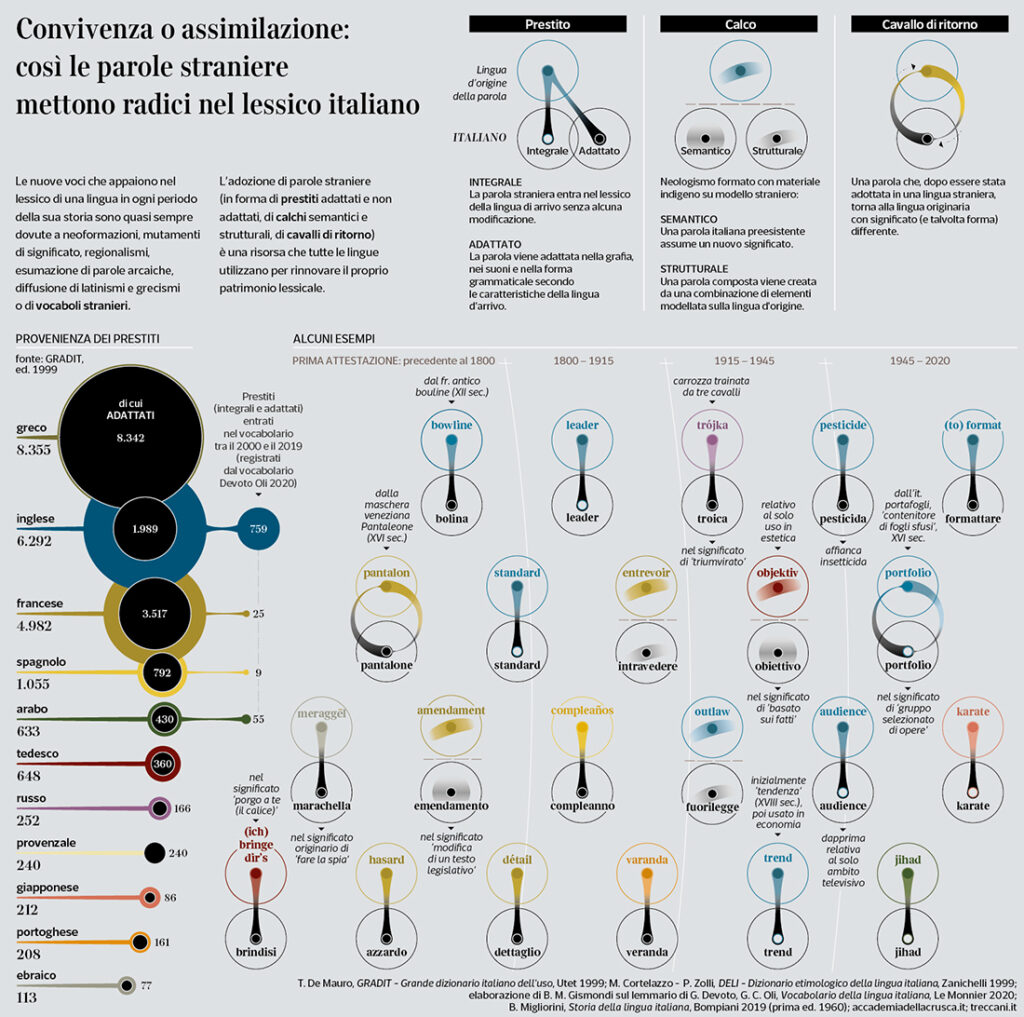

Historical layering of loanwords

in Italian

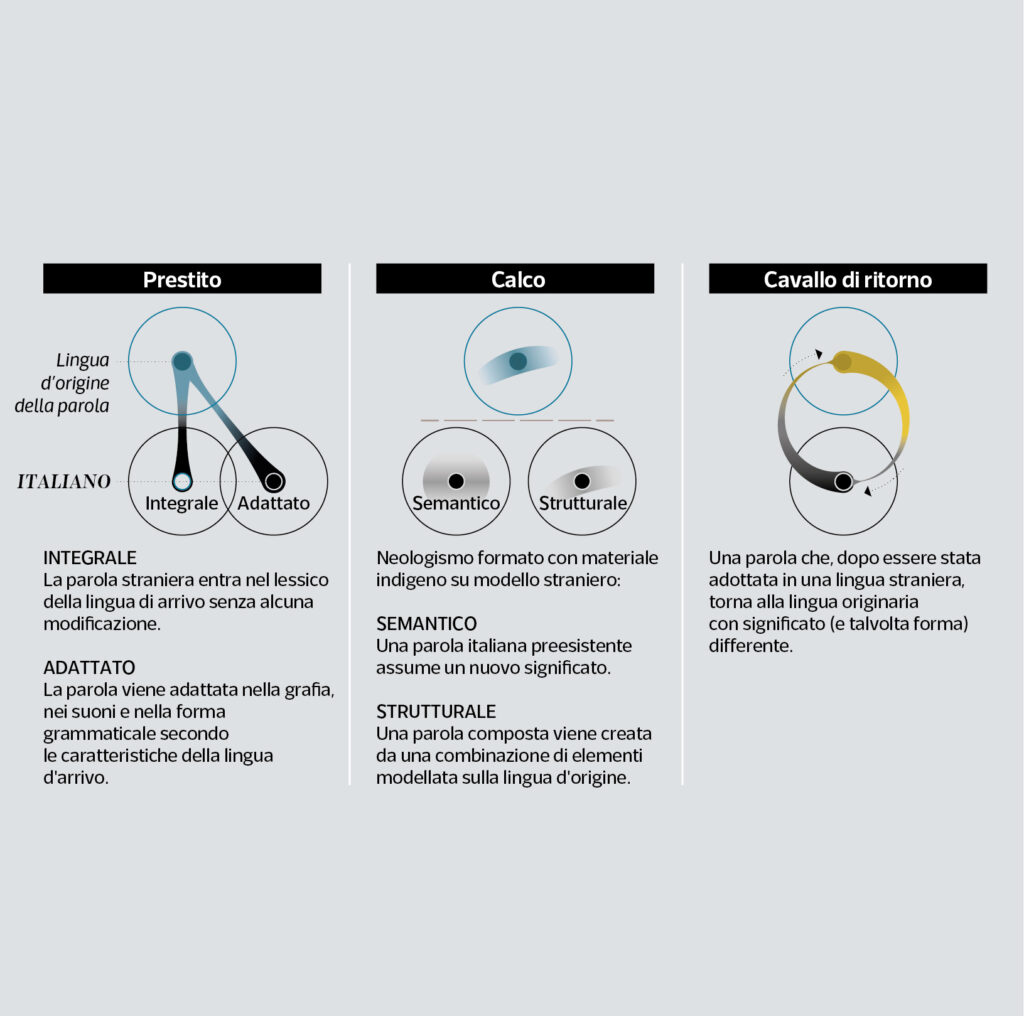

Linguistics defines a loanword as a foreign word used in a language other than the source language.

The various branches of Linguistics concerned with language contact phenomena distinguish between integrated loans, non-integrated loans (or importations), and substitutions, which may have internal variations (loan creation, l. rendering, l. translation or calque, reborrowing, etc).

As far as Italian is concerned, thirty-five years ago Arrigo Castellani spoke resoundingly of ‘morbus anglicus’, i.e. the invasion of words borrowed from English into Italian use: a virus supposedly capable of infecting and corrupting the Italian language, in particular through non-integrated loans. And many years before, fascism had already reacted by creating the influential “Commission for the Italianness of the Language” of the Royal Academy which outlawed so-called ‘barbarisms’, especially in journalistic language and shop signs. One of the biggest scientific blunders to date, in this subject matter.

Careful studies and accurate and extensive knowledge of social phenomena connected to language have allowed a balanced scientific position to be established, which today believes, beyond the saturation in some sectoral languages such as information technology, even for languages that have been affected since their birth by centuries of interference, that the legacy of non-adapted words is usually small and that, apart from any puristic considerations, the senses ‘imported’ by non-integrated loans are normally well assimilated while the morpho-syntactic structure is just slightly touched: that is, those senses are neither numerically nor qualitatively capable of polluting nor of “barbarizing” the lexicon of the receiving language, but they can at most characterize some specialist fields.

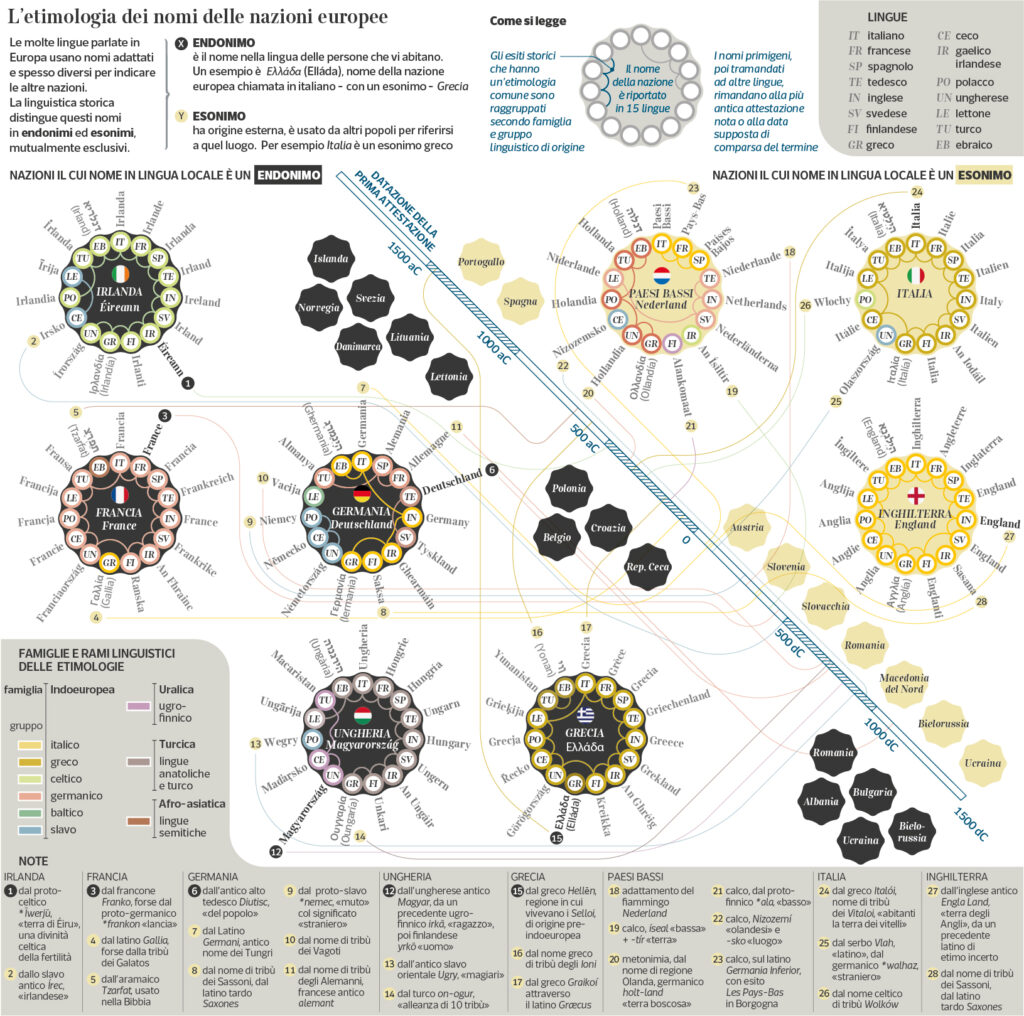

Etymology of names of the European nations

This visualization shows the name of many European countries in their national language and the name used to call them in 15 European languages. As many of those names given in other languages have a common origin, they also share the same etymology, which is clustered together to evidentiate the linguistic group and family it comes from. Each primitive name is then reported in the note section on the bottom. These primitive names, then handed down to other languages, refer to the most ancient attestation note or presumed date of appearance of the term. The attestation is connected on a timeline that crosses the infographics along the diagonal. The nations and their names appear in black when they are endonyms and yellow when exonyms.

These two terms, coined in contrast to each other, are what geography and cartography hold as the “official name” of a locality (or in general, of a geographical entity). But they are also used in Linguistics.

Endonym is the name of a nation, or more generally of a geographical feature, in an official or well-established language occurring in that area where the feature is situated. Examples: Vārānasī (not Benares); Aachen (not Aix-la-Chapelle); Krung Thep (not Bangkok); Al-Uqşur (not Luxor).

Exonym is, in contrast, the name used in a specific language for a feature situated outside the area where that language is widely spoken, and differing in its form from the respective endonym(s) in the area where the feature is situated. Examples: Warsaw is the English exonym for Warszawa (Polish); Mailand is German for Milano; Londres is French for London; Kūlūniyā is Arabic for Köln. The officially romanized endonym Moskva for Mocквa is not an exonym, nor is the Pinyin form Beijing, while Peking is an exonym.

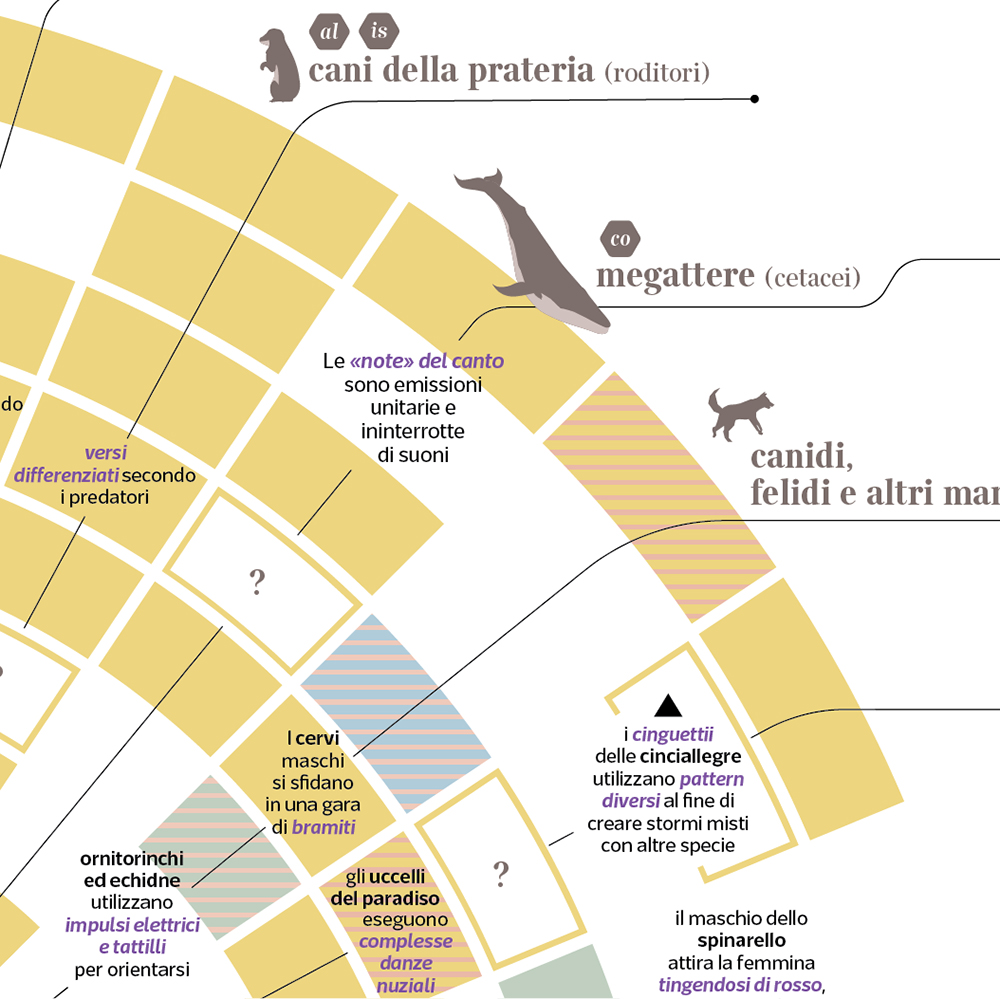

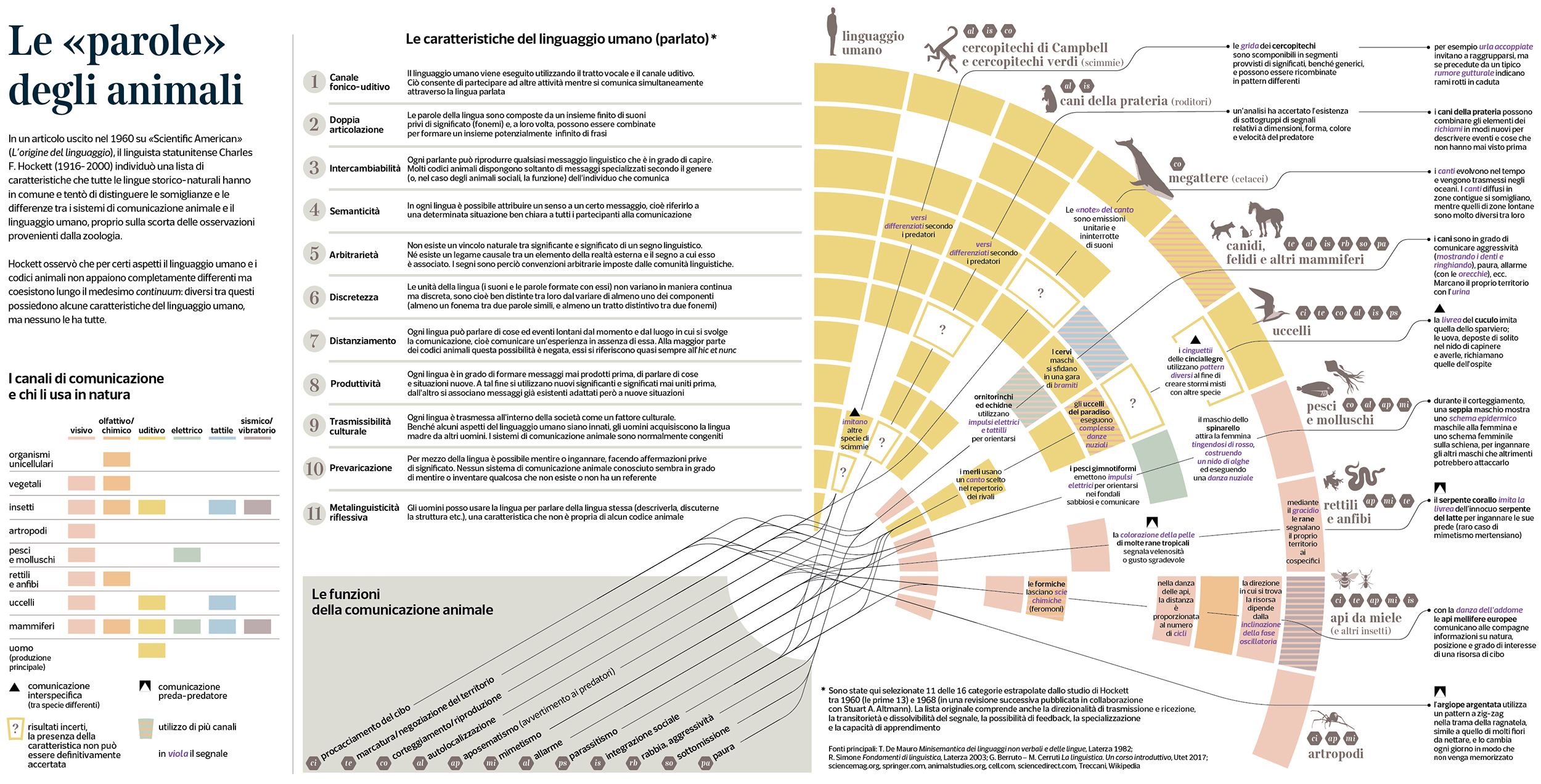

Animal “words”

This is a comprehensive, visual evaluation of communication in the animal kingdom and how it compares with human language

The set of ‘design features‘ which was proposed by Charles F. Hockett in the 1960s remains probably the most influential means of approaching animal communication and evaluating how it compares in its many forms with human language. Although Hockett’s perspective was restrained by his focus on the code itself rather than the cognitive abilities of its users, some of his observations still look astounding.

First, the overall vision interpreted as a vantage point:

‘Although the comparative method of linguistics, as has been shown, throws no light on the origin of language, the investigation may be furthered by a comparative method modeled on that of the zoologist. The frame of reference must be such that all languages look alike when viewed through it, but such that within it human language as a whole can be compared with the communicative system of other animals […]’

This comparative assumption is the starting point for American structuralist linguistics to create a list of the so-called universals of human language, taken up and expanded several times. Such extensive variability – among the thousands of languages spoken in the world – is reduced to a few fundamental assumptions when faced with the communicative capabilities of the animal world. They are also very extensive but on a very limited range of possibilities.

Secondarily, Hockett made clear how these features connect to form systems that have a clear communicative functionality, some of them being even open systems, which means, new signs can be created inside them.

And this brings the focal point to language functions. The non exhaustive list on the right on brown background covers a wide spectrum of animal behaviors, including some that were once retained as human-specific (e.g. fabrication).

Contrary to Hockett’s view, another distinguished US structural linguist, Noam Chomsky, has a radically different position on animal communication. According to Chomsky, language has developed to be used for many functions, but not purposefully for communication among human beings, or not only for that reason, as evidence of the importance of the so-called ‘inner speech’ is so overpowering.

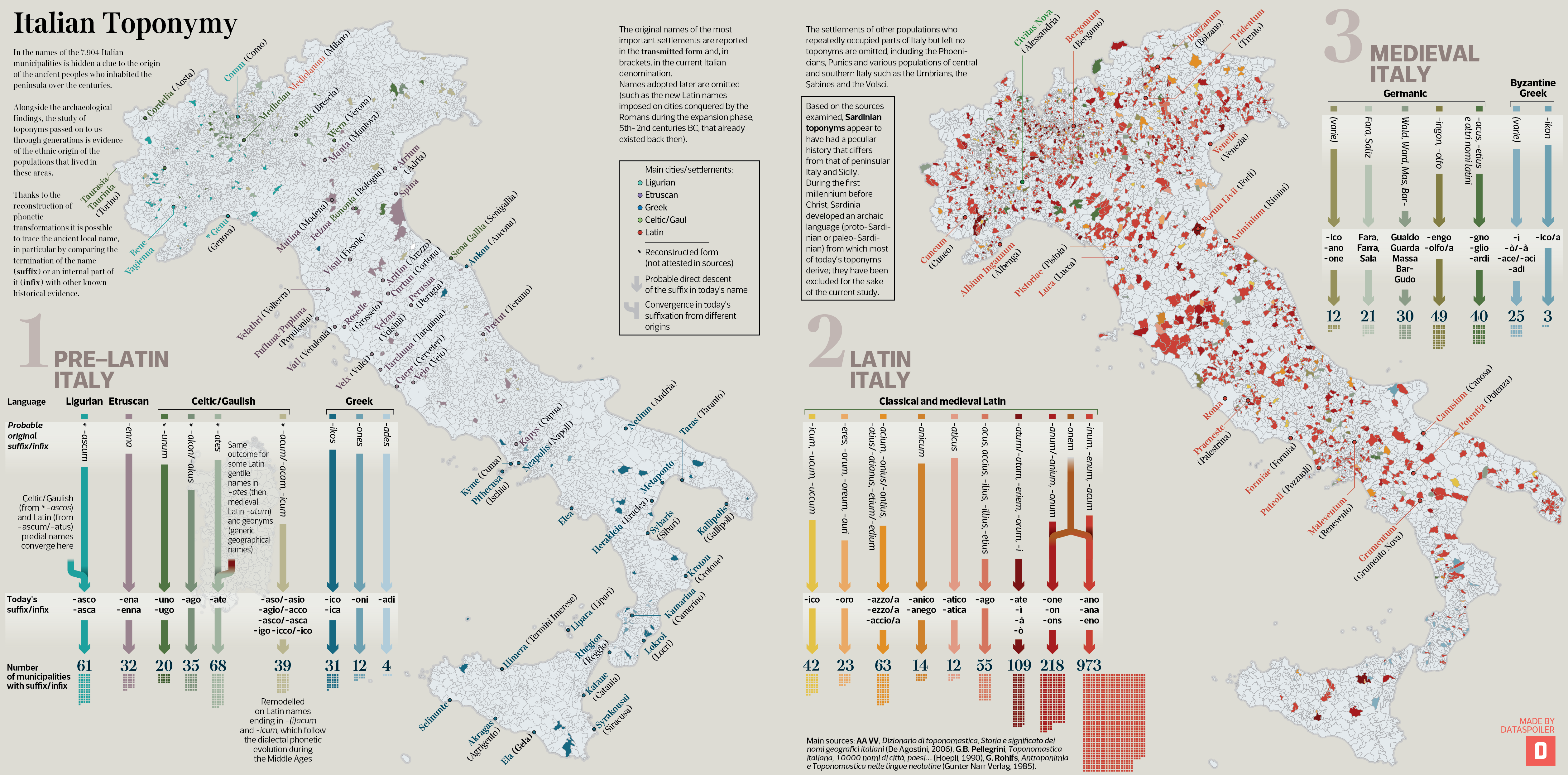

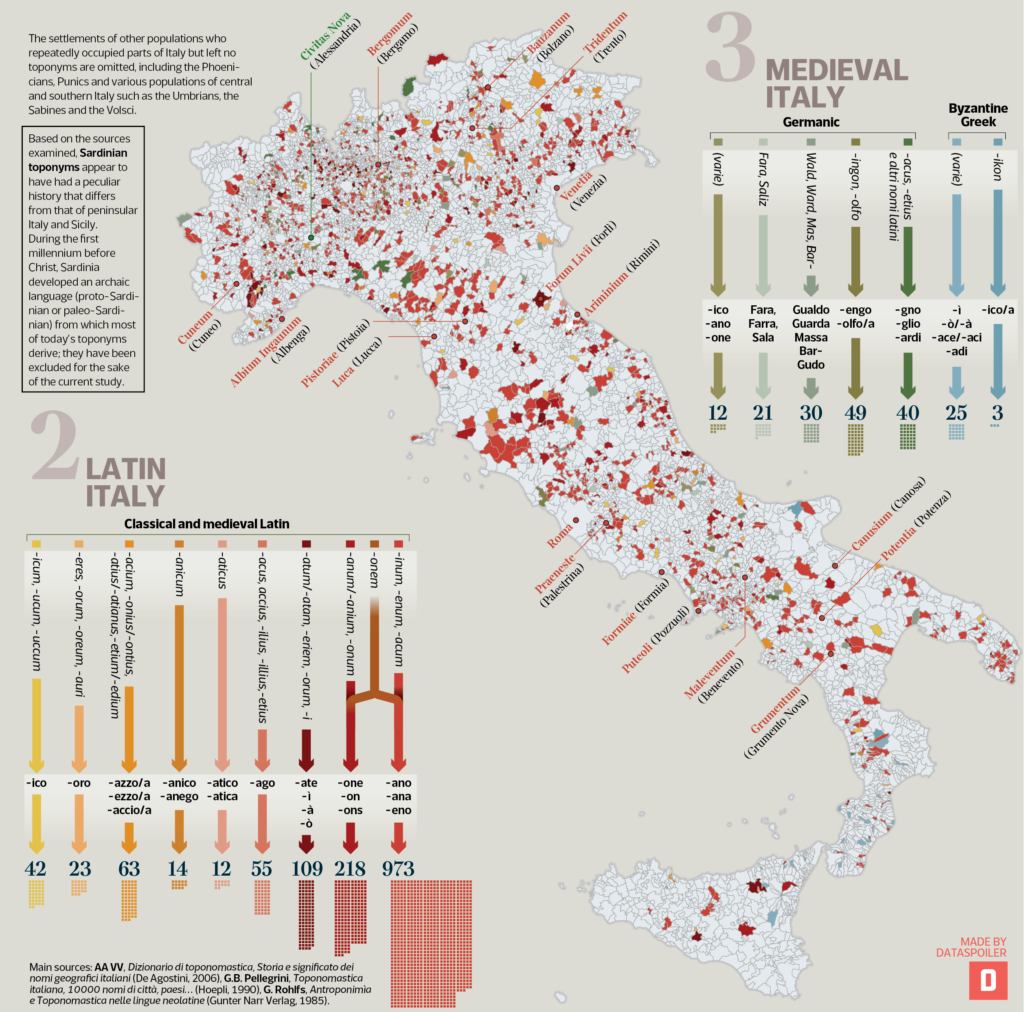

Italian Toponymy

As the very first piece of the ‘Visual Linguistics’ series, this was quite an important cornerstone. It appeared on Corriere della Sera – La Lettura insert on April, 2020.

The visualization shows the municipal place names for which it is possible to suppose a genesis arising from a known ancient language, and therefore connect the foundation of each settlement to a specific population, either it was pre-roman, or coheve, or ensuing the Western Roman Empire in the Middle Ages.

The toponyms are grouped together according to three historical phases (Pre-Latin, Latin and Medieval Italy) in which they would have originated, and reported on the current municipality border map whenever they retain their trace in the form of the termination of the name (suffix) or internal part (infix). The total figure for each category is displayed at the end of the arrows.

Original names of the most important settlements are fully shown on the map in the form transmitted (and in brackets in the current Italian version). The names subsequently adopted are omitted (e.g. such as the new Latin names imposed on existing cities, which the Romans conquered during the expansion phase, 5th-2nd century BC). For the sake of simplicity, Sardinia, whose original language (Protosardo or Paleosardo) is poorly known, has been excluded.

The populations considered: Ligurians, Etruscans, Greeks, Celts, Latins, Byzantine Greeks, Germanic populations (in particular Longobards and Goths). Settlements (and toponymic outcomes) of other populations that on various times occupied parts of Italy, including the Phoenicians, Umbrians, Sabines, Volsci, are left out.

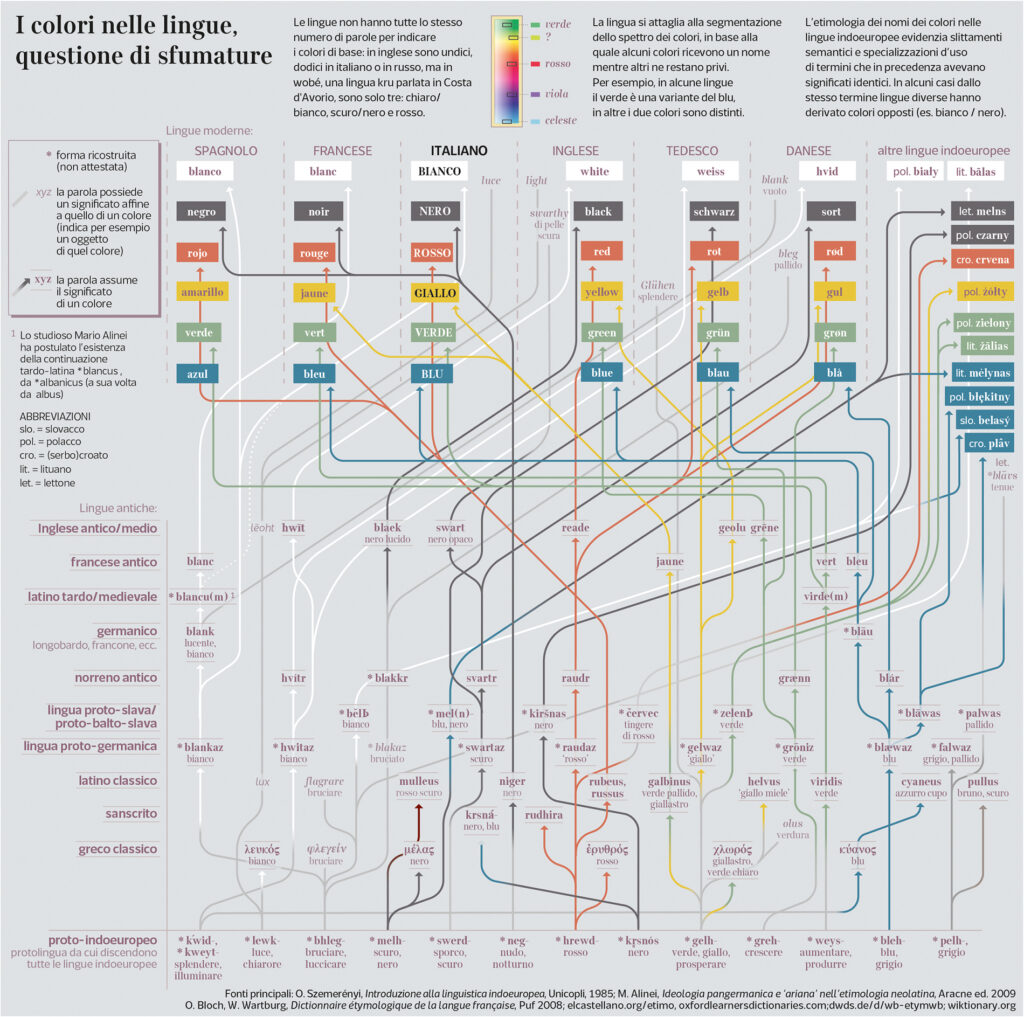

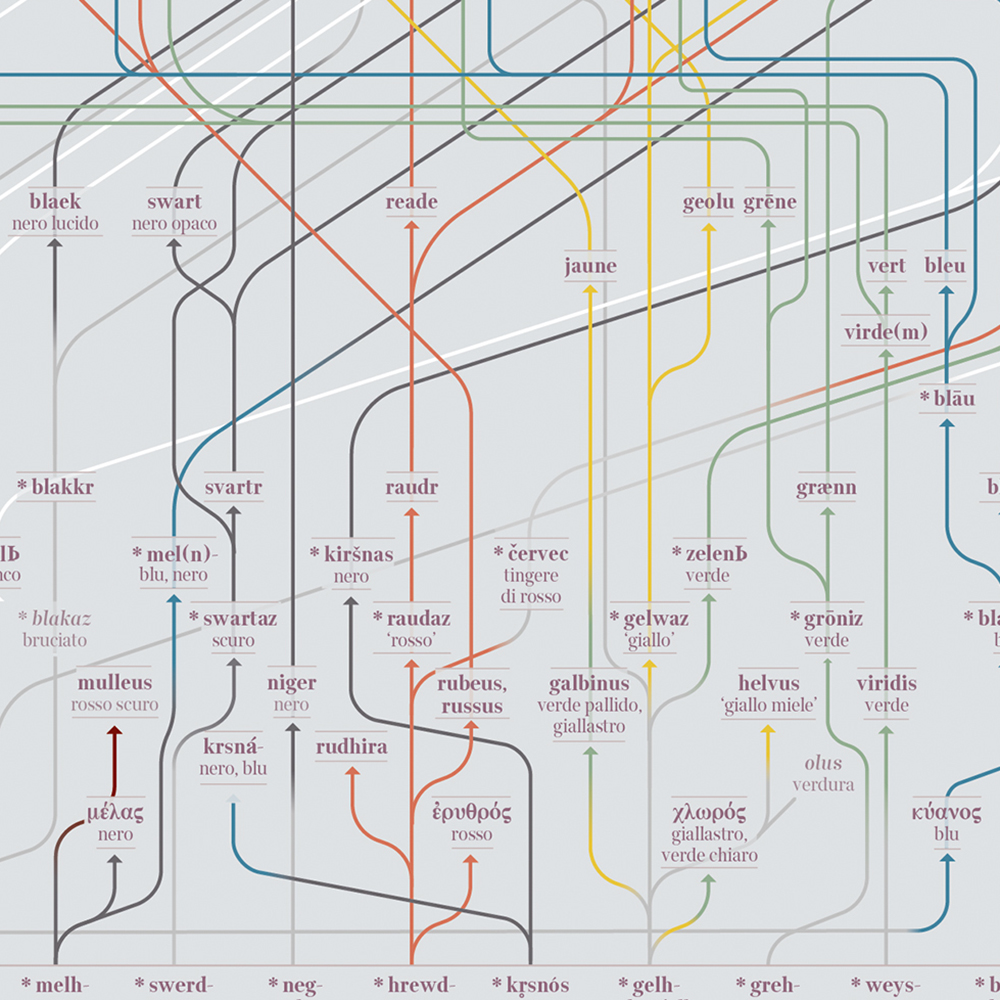

Colors in languages, a nuanced issue

This visualization – publixhed on Il Corriere della Sera – La Lettura on March 2023, inspect how colors are named and used in some contemporary European languages, and how they matured and came to our modern world through ages of semantic shifts and specializations of use.

As a corollary of the concept that colors are a subjective reality – or tritely, a matter of perception – synchronic studies in Linguistics reveal how different languages offer different segmentation of the color spectrum, namely the range of physical properties of objects concerning their tint; and how photoreceptors in our eyes catch them and transmit the information to neurons and finally to our brain for further classification.

It comes to mind the renowned case of Kalaallisut, an Eskimo–Aleut language spoken by around 57,000 people in Greenland, who are reportedly able to name 21 different types of white connected to 21 different types of snow. While this myth has been debunked by anthropologist Laura Martin in the eighties, it is still remarkable how different languages distinguish a different array of basic colors, particularly in regards to their number: in English they are eleven, twelve in Italian and in Russian, but in Wobé, a Kru language spoken in the Ivory Coast, there are only three: light/white, dark/black and red. In some languages, green is a variant of blue, in others the two colors are distinct. So things get more and more complicated.

In 1969, two researchers at the University of Berkeley, Bren Berlin and Paul Kay, published groundbreaking research, postulating that every culture in human history has invented the names and classification of colors in the same order. According to the study, the names of the basic colors in each culture (and therefore in each language) could be predicted based on the number of colors that have a specific name, as long as they are mono-lexematic and mono-morphematic (for example ‘red’, not ‘dark red ‘ nor ‘reddish’), just in that language.

If a language has only 3 names of color, these will always be white (or light), black (or dark), and red; if there are 4 names, they will be white, black, red, and yellow or green; if there are 6, they will be white, black, red, green, yellow and blue, and so on. Over time languages would evolve, sequentially acquiring new terms for basic colors; if a basic color term is found in a language, the colors of all previous phases should also be present. The study was based on identification tests of 330 colors (according to the Munsell system of colors), to which 20 speakers of different mother tongues were subjected. The classification of colors in these 20 languages gave out mixed results, which matched the thesis of Berlin and Kay.

Berlin and Kay’s study was repeatedly criticized in the following years, due to shortcomings in research methodologies and the excessive weight granted to the subjective perception of the interviewees. Many exceptions to the universal rule identified by the authors were reported. However, the research is still funded by an American universitarian institute, and the suggestions raised are still used in recent studies on the visual perception of newborns and on the formation of language structures and their historical evolution.

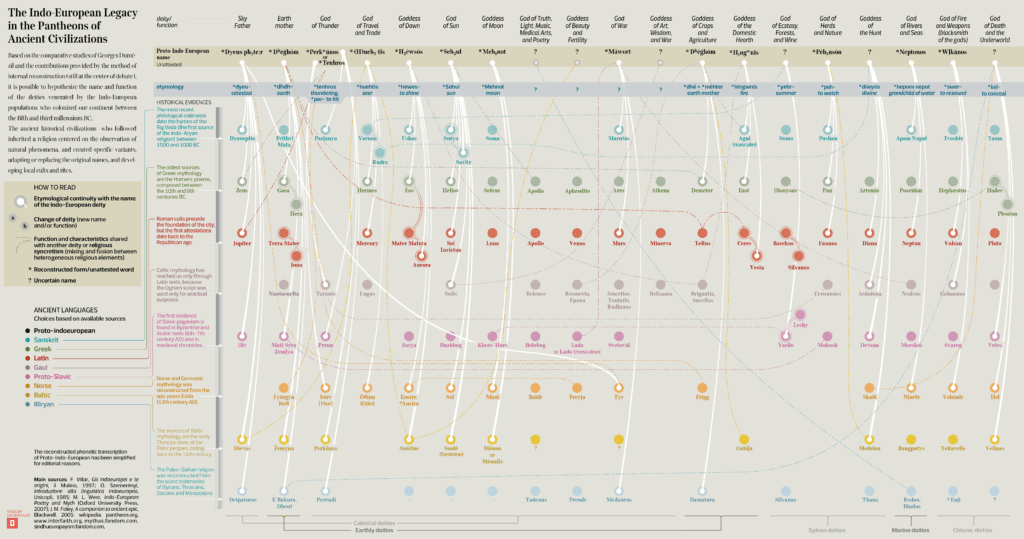

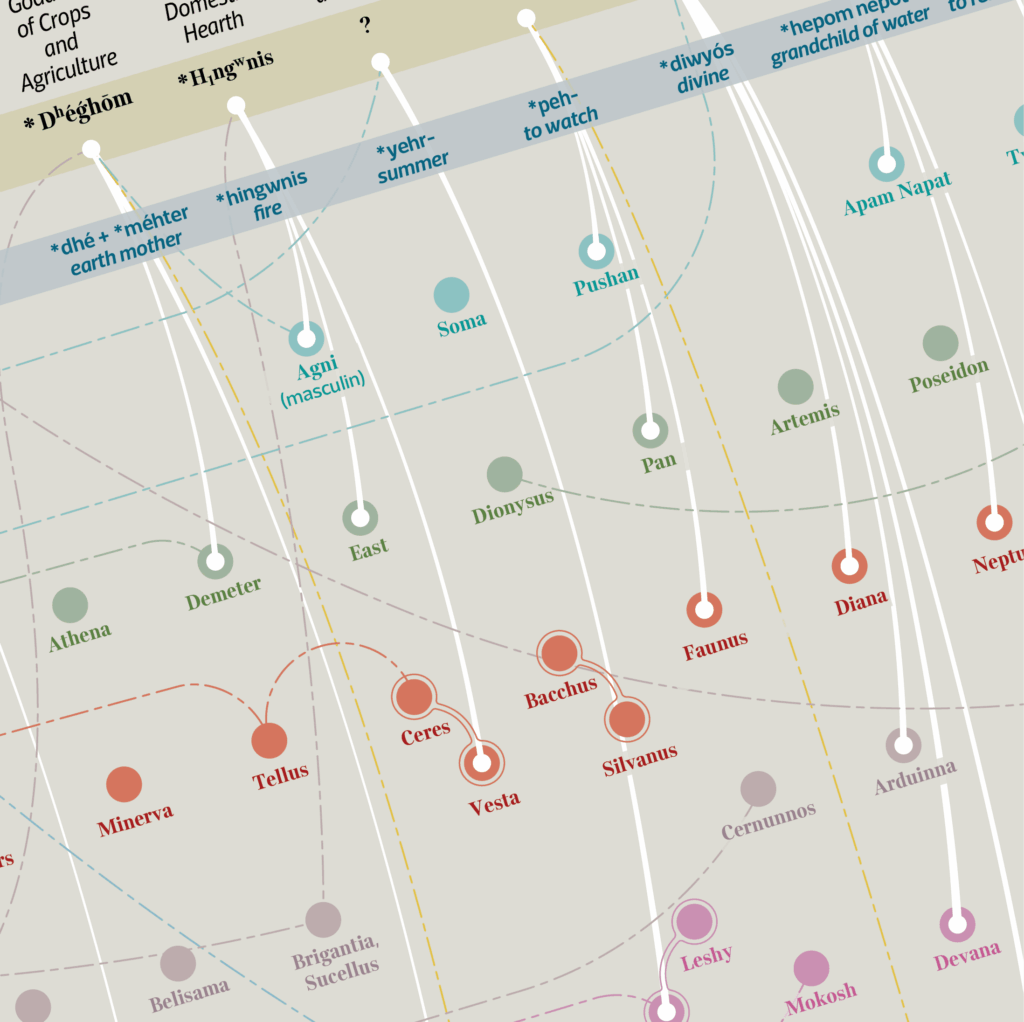

THE INDO-EUROPEAN LEGACY IN THE PANTHEONS OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

The visualization depicts the most important known lineages of the supposed Proto-Indo-European religion down to the names of the deities worshipped by a few historical civilizations.

For each Indo-European deity, the function, the reconstructed name, and the etymology (noted in blue) are reported. The white connections trace the root to the names of later European deities. Dotted lines indicate the syncretistic relationships between related cults or their historical transformation.

Since the dawn of Positivism and over the last two centuries, the study of the etymological relationships between the ancient historical civilizations and a supposed common ancestor population, Indo-Europeans, has raised increasing interest among scholars and archeologists.

However, the Indo-Europeans, who probably came to Europe from the steppes of present-day Ukraine in multiple migrations from the 5th to the 3rd millennium B.C., left no archaeological remains. One of the methods available to historians to reconstruct any relationships is internal reconstruction, which is a particular branch of diachronic linguistics that deals with comparing evidence found in later languages, obtaining possible evolutionary lines, and reconstructing the

fragments of a lost language.

However, the reconstruction of a unique Indo-European religion, among a few other topics, can still give us some shards of knowledge regarding our roots.

Optimists argue that the name should be associated with the function that the divinity performed in each specific civilization, and in some cases also with the symbolism associated with its worship. This way, many connections can be established.

There are risks of underestimating or, on the contrary, overestimating the few records attested in both positions: from the excessive weight attributed to the meaning (an error that pre-scientific etymology typically ran into), to the arbitrary backdating of all etymologies up to a single date, when it is probable that the waves of Indo-European colonization were at least three, in the span of 1500 years.

It appears probable that a population from the steppe, formed by shepherds and at the mercy of rain and storms, together with their cattle, practiced the cult of the sun as they needed its rays, the cult of fire because they craved its warmth and protection from predators, and worshipped other deities capable of administering the rain, controlling the wind, illuminating the darkness. Some of these cults soon turned into local rites; others lasted much longer among some populations, up to historical times, as in the case of the sun among the Germans and the ancient inhabitants of Scandinavia, or its stylish representations such as the svastikas (the name has Sanskrit origin indeed) which later turned into meaningless emblems in the riverbed of various historical religious traditions.

Personification is probably the process that led to the constitution of the whole sky in a divine father, and consequently of his conversion into a mother (Mother Earth), considered as the other half of the universe. Similarly, in son- and daughter-deities, all the minor natural epiphanies are contained therein. This is evidenced by the probable etymology of the generic name ‘god’, PIE *deiwos: Sanskrit devás, Avestian daeva, Latin deus, Old Celtic Deva, Lithuanian Dièvas, Old Norse Tivar (plural). *deiwos is nothing more than an adjective, that gave the name of the father god / celestial vault *dyéus; we could translate it as ‘celestial’, not in the transcendent sense (not meaning ‘heavenly’) but in the ‘atmospheric’ sense.

(based on F. Villar, Los indoeuropeos y los orígenes de Europa. Lenguaje e historia, Italian edition, 1997)

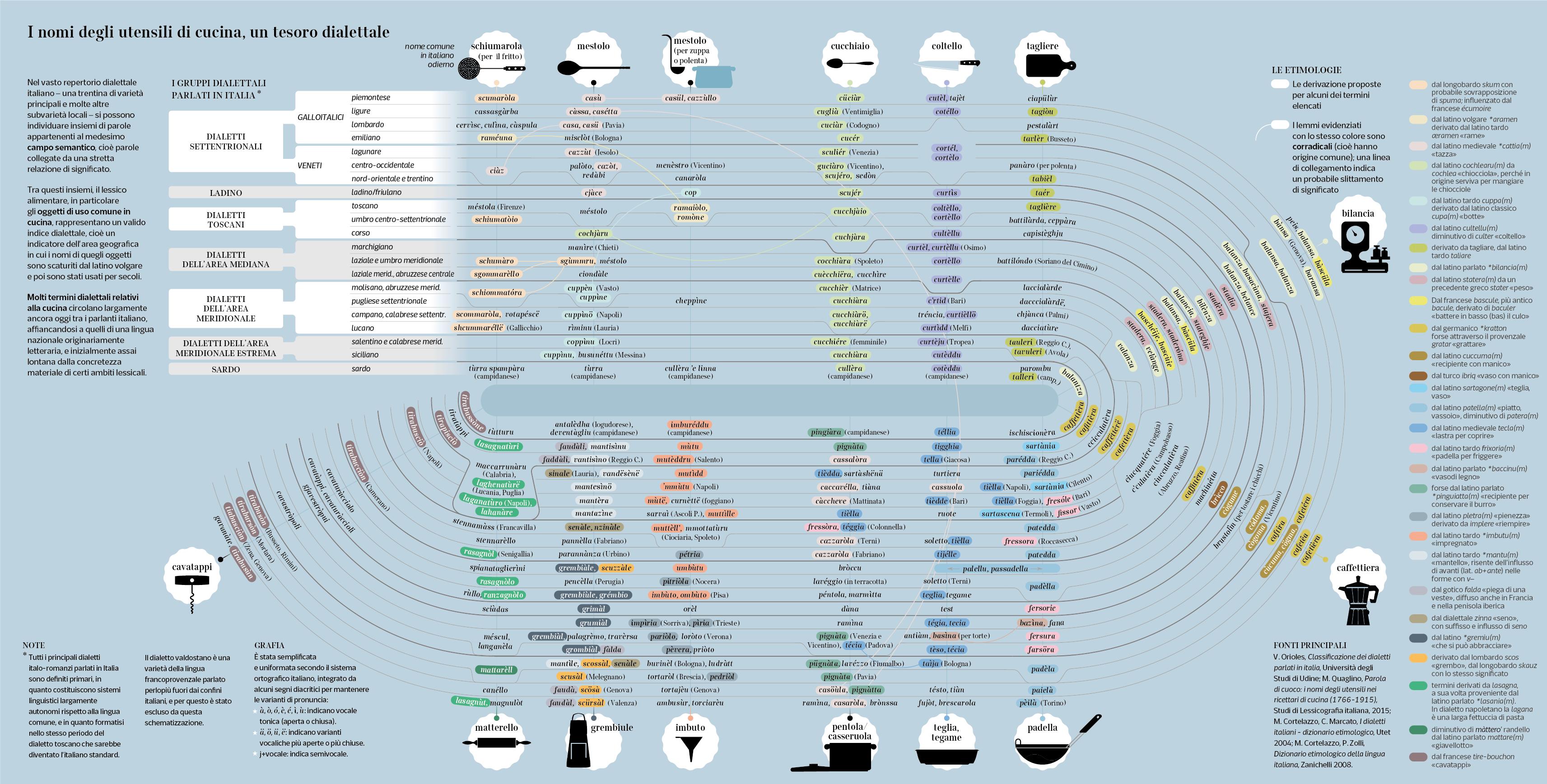

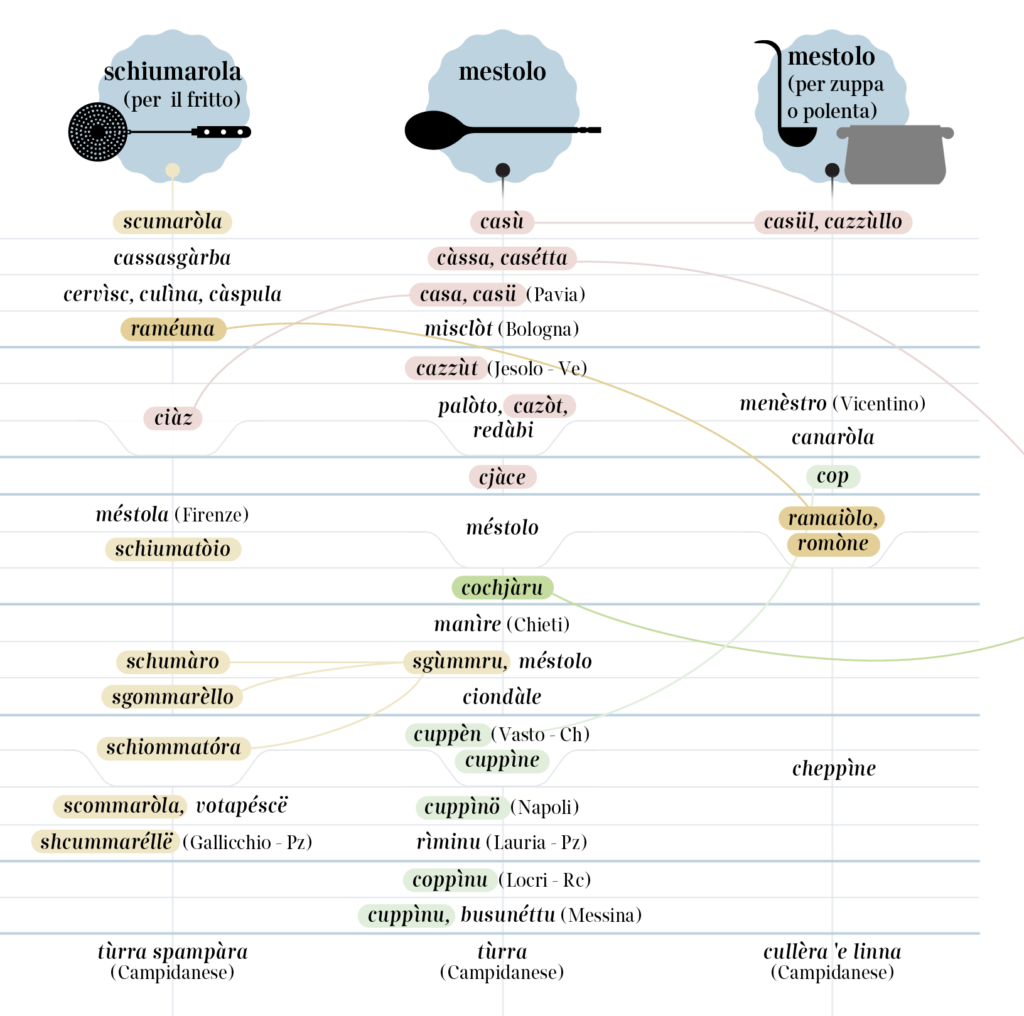

Among kitchen utensils, a treasure

of dialectal names

In Italian, the richness of the dialect names for kitchen utensils is truly amazing.

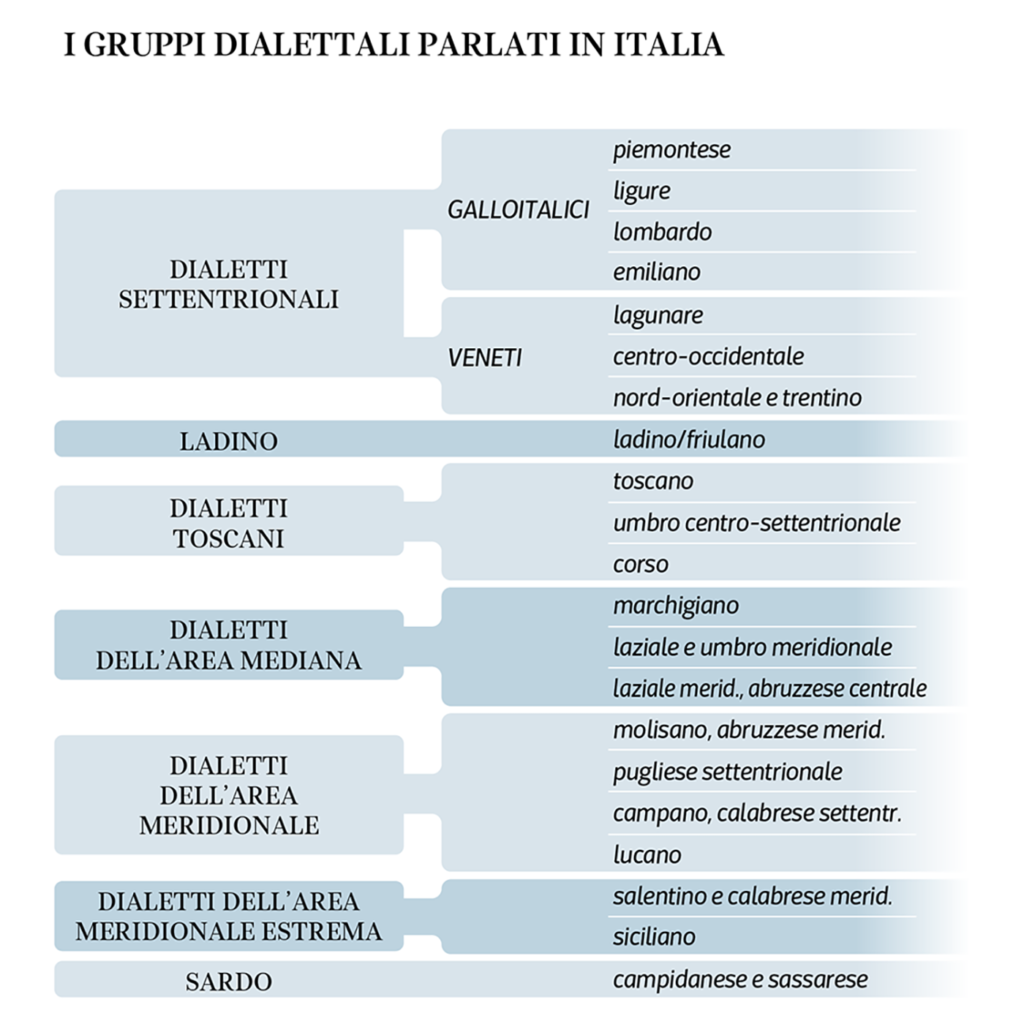

The dialect variants spoken in Italy have been the subject of scientific classification attempts since the late nineteenth century. In the most recent and accredited classifications, such as that of G. B. Pellegrini, the Italian language returns to being the most significant reference and criterion of distinction. Even more recently, dialect speeches have fallen significantly behind in use and diffusion to the advantage of the so-called regional Italians, i.e. varieties of the standard language influenced by the underlying dialect phonology and sometimes by localisms blatantly emerging in the lexicon. The comparison takes place between a language – originally a literary language – which has long been codified (Italian) and another language – dialect, mainly a spoken language – now subordinated to the first, from a social point of view, with the sole exclusion of small areas of the territory.

In a context of coexistence and co-occurrence, it has been Italian itself that paradoxically defended dialects, especially in specialized areas. This is the case of the gastronomic lexicon (e.g. many vegetables have different common names in various Italian regions and origins that date long back). In this small study based on scientific sources, a specific sector of the semantic field relating to food, namely that of the common names of kitchen objects, has been investigated. These names are influenced by the long culinary traditions handed down orally, by the care for social and material culture, and by the concreteness of the objects to which they refer, thus constituting a privileged field for dialectological investigation.

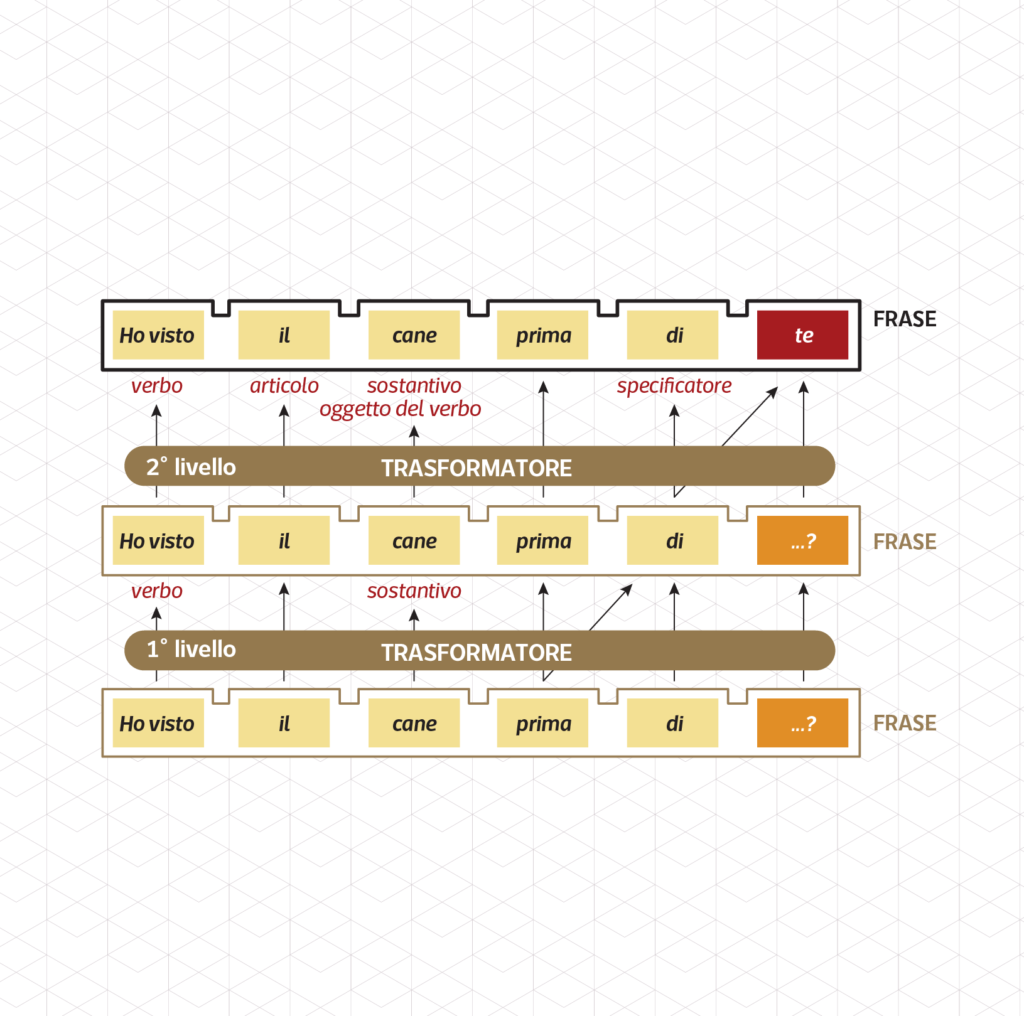

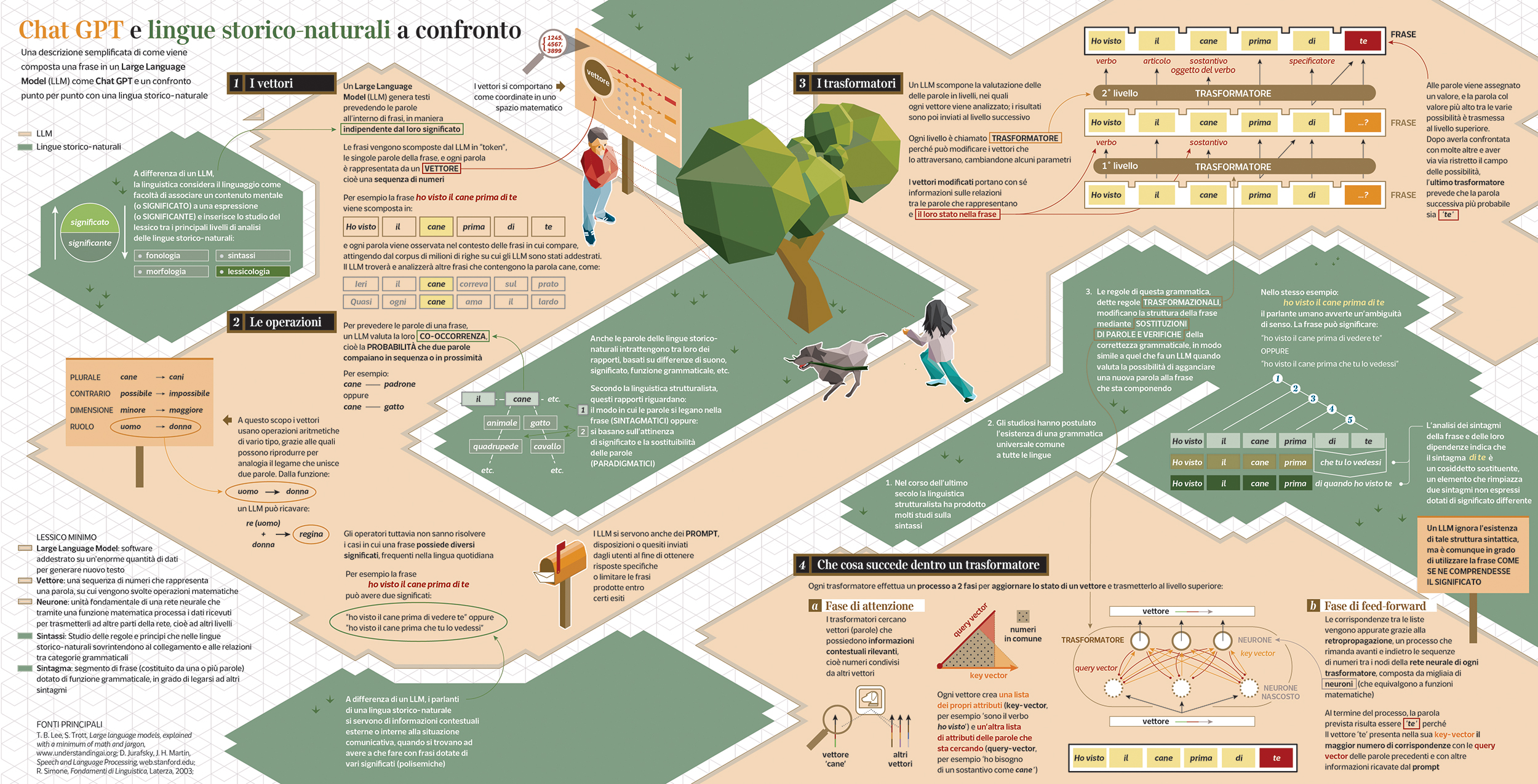

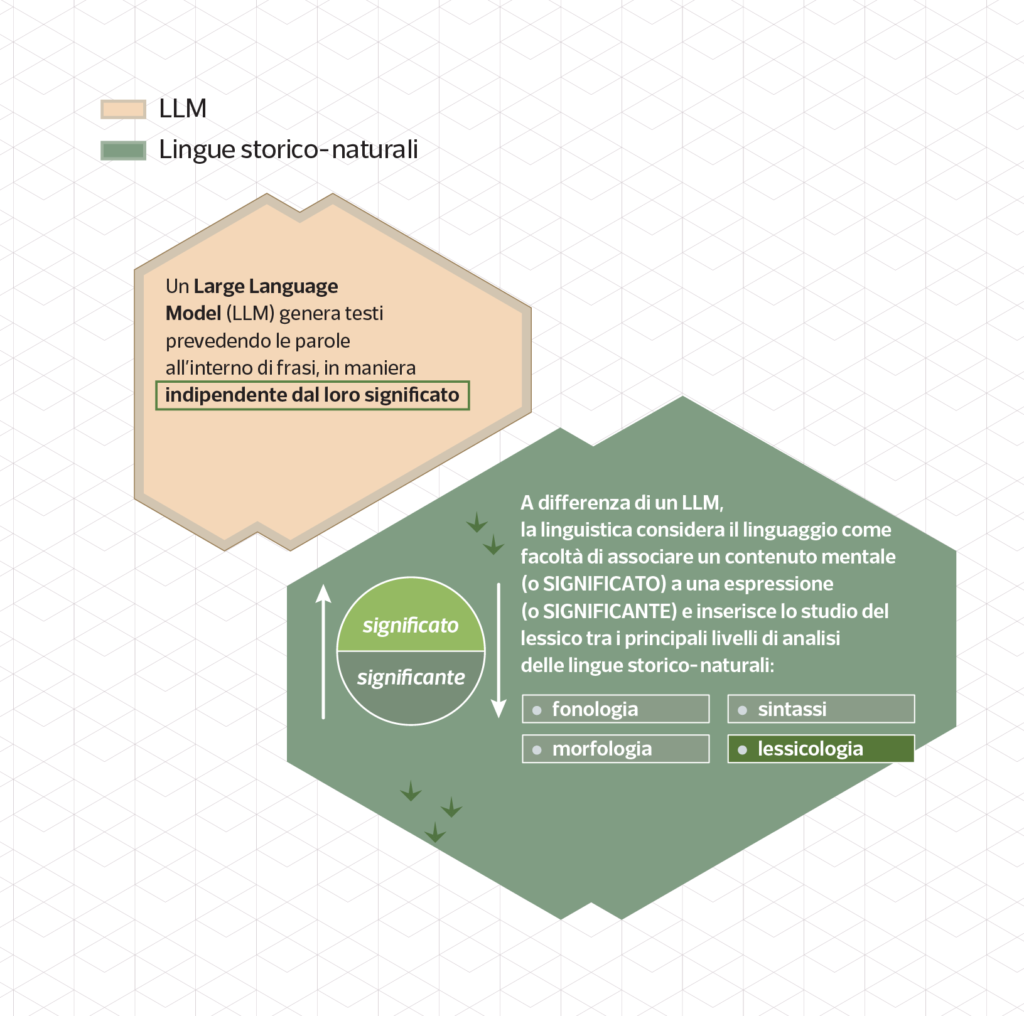

LLM and natural languages compared

This visualization tries to explain the process an LLM undergoes when generating a sentence, and compares the same process when performed by a human (from the point of view of structuralist linguistics).

Large Language Models have been in the limelight since the release of ChatGPT, with new versions being announced every few months since November 2022. By the time of Chat GPT debut, the usage of generative LLMs thrust into the routine work parties of big companies while conquering the cover pages of all the newspapers around the world (which one by one are now denying permission to train such LLMs on the content they publish).

But few seem to know how an LLM actually churns out words. This infographic primarily tries to fill the apparent lack of information regarding the process that an LLM goes through while producing seemingly human language.

The second goal of this infographic is to set this generative process against natural (human) language, namely the language we speak for everyday use. Generations of scholars forged an array of models for representing how linguistic signs are formed and commanded, finally paying attention to contextual information and nuances of meaning from the second half of the twentieth-century on.

Without dwelling on criticisms (like the well-founded accusations of systematic plagiarism boosted by technological progress), it is important to note how the public debate on the potential of this tool ceased one step away from reawakening a twentieth-century debate on the transmission of meaning through human language, its definition, and nature.

Looking at the various achievements reached by some notable scholars (for example Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics, or Wittgenstein’s late works), it seems naive to rule out completely that LLMs can use meaning like we do and therefore they would be limited to mimic how humans use meaning.

In his late Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein states “In particular, for a large class of cases, although not for all, in which we use the word meaning, it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language; the meaning is a function of use, but of a socially regulated and coordinated use, and not of personal, individual use; knowing the meaning of a sign means knowing the conditions of use of that sign, therefore the meaning is systematic (not at the mercy of individuality) and is in connection with the socio-cultural context”.

So, what does it mean to use meaning, in its most general definition, if not to know how to use words and connect them in such a way as to convey a sense that is recognizable by the community of speakers? And how exactly is the way an LLM uses meaning different from this?

The answer likely lies in considering the meaning as purely contextual.